What is Hibernation?

Table of Content

Winter Sleep

Hibernation vs. Torpor

Preparation for Hibernation

Physiological Changes

Energy Utilization

Exit from Hibernation

Examples of hibernating animals

Winter Sleep

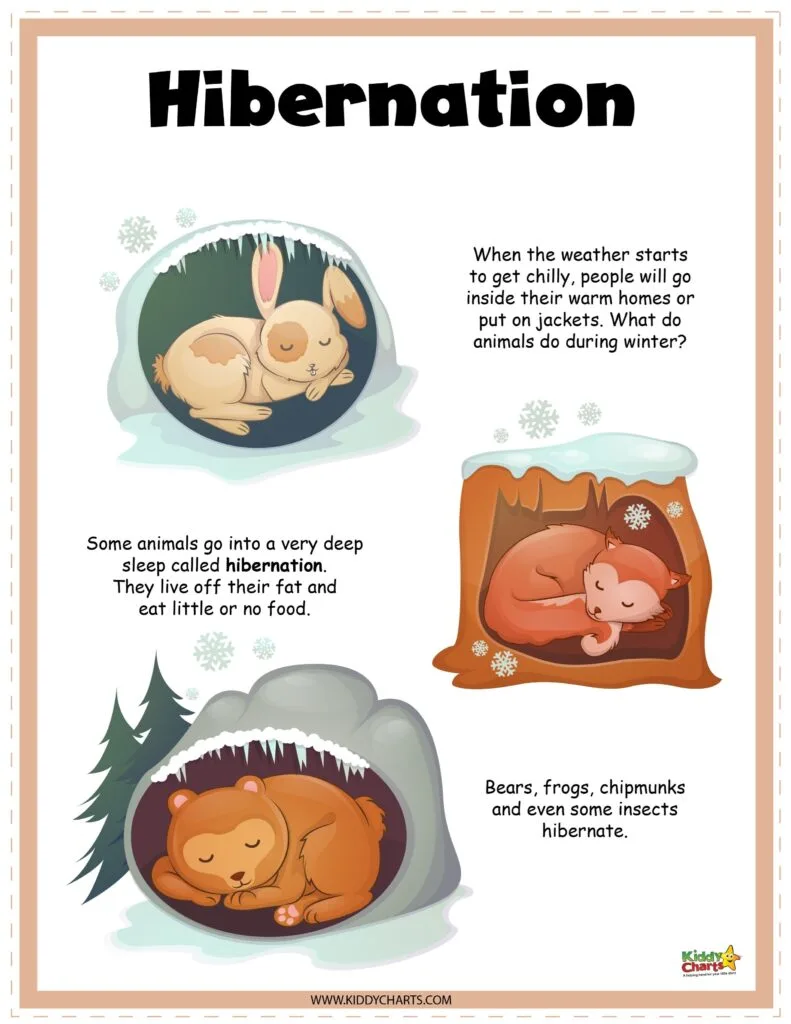

Hibernation is a state of deep sleep or dormancy that some animals enter into during the winter months or periods of adverse environmental conditions, such as extreme cold or food scarcity. It is a survival strategy that allows these animals to conserve energy and reduce their metabolic rate when resources are scarce and conditions are harsh.

Hibernation is not the same as sleep, as it involves a much deeper and more prolonged period of inactivity. While in hibernation, an animal’s vital signs, such as heart rate and breathing, are significantly reduced, and they are generally unresponsive to external stimuli. They can remain in this state for weeks or even months, depending on the species and environmental conditions.

Hibernation vs. Torpor

Hibernation and torpor are two distinct states of dormancy employed by animals to conserve energy, but they differ in several key ways.

Hibernation:

Duration: Hibernation is a prolonged state of dormancy that can last for weeks or even months, typically during the winter months when resources are scarce and environmental conditions are harsh.

Metabolic Rate: During hibernation, an animal’s metabolic rate drops significantly, with a substantial decrease in body temperature, heart rate, and overall activity. Some hibernators’ body temperatures can approach the ambient temperature.

Consistency: Hibernation is generally a more predictable and stable state compared to torpor. Animals enter hibernation for an extended period, and their metabolic rate remains low throughout.

Arousals: Hibernators may experience periodic arousals, during which they briefly wake up, raise their body temperature, and may even eat from their stored food reserves. These arousals are less frequent compared to torpor.

Torpor:

Duration: Torpor is a shorter-term, daily or nightly state of dormancy. It is often used by animals to conserve energy on a daily basis, primarily during periods of low activity, such as nighttime or when food is scarce.

Metabolic Rate: Torpor is characterized by a temporary reduction in metabolic rate, heart rate, and body temperature. However, these reductions are not as drastic as those seen in hibernation.

Consistency: Torpor is an episodic and intermittent state. Animals enter torpor on a daily or nightly basis, and their metabolic rate can return to normal when they are active.

Arousals: Torpid animals frequently enter and exit this state. They may experience daily bouts of torpor during which they reduce their energy expenditure, and then they become active again when conditions are more favorable.

Preparation for Hibernation

Before entering hibernation, animals go through a period of preparation. This phase typically occurs in late summer and early autumn when food is more readily available. Hibernators need to accumulate sufficient energy reserves to sustain them throughout the dormant period. They do this by increasing their food intake and converting excess calories into fat, which serves as their primary energy source during hibernation.

Physiological Changes

Hibernation involves a series of dramatic physiological changes. These changes include a substantial drop in body temperature, a significant reduction in metabolic rate, slowed heart rate, and minimal physical activity. These adaptations help hibernators conserve energy when food is scarce or environmental conditions are harsh.

During hibernation, an animal’s body temperature drops significantly, and its metabolic processes slow down to a minimal level. This reduced metabolic rate helps them conserve energy because they do not need to eat as frequently or move around as much. Hibernating animals often find a sheltered and secure location, such as a burrow, cave, or hollow tree, to spend the winter months.

Energy Utilization

Throughout the hibernation period, animals rely on their fat stores for energy. The metabolic slowdown allows them to survive on these reserves without needing to eat or drink. The efficiency with which hibernators utilize their energy stores is a testament to the incredible adaptations that have evolved over millions of years.

Exit from Hibernation

As winter comes to an end and environmental conditions improve, hibernating animals gradually exit hibernation. They begin to warm up their bodies, increase their metabolic rate, and become more active. The exit process is just as carefully regulated as the entry, ensuring a smooth transition back to a fully active state.

Examples of Some hibernating animals

Bears: Bears, such as black bears, grizzly bears, and polar bears, are well-known hibernators. They enter a state of reduced metabolic activity during the winter, lowering their heart rate and body temperature.

Groundhogs: Groundhogs, also known as woodchucks, hibernate through the winter in burrows. They enter a state of torpor, during which their body temperature and metabolic rate decrease significantly.

Bats: Many bat species hibernate in caves, abandoned mines, or other sheltered locations during the winter. They can enter a deep hibernation, during which their body temperature drops close to the ambient temperature.

Hedgehogs: Hedgehogs hibernate during the winter months. They find a sheltered spot, often in a nest of leaves, and their metabolic rate drops to conserve energy.

Dormice: Dormice, particularly the hazel dormouse in Europe, hibernate in nests or tree hollows. They spend about half of the year in hibernation.

Chipmunks: Chipmunks enter a state of torpor during the winter, usually in underground burrows. They wake up periodically to feed on stored food.

Snakes: Some snake species, like the Eastern Massasauga rattlesnake, hibernate in dens or burrows to escape cold temperatures. They become less active and rely on their body’s energy reserves.

Turtles: Aquatic turtles and some terrestrial turtles hibernate in the mud or at the bottom of ponds and lakes. Their metabolic processes slow down to endure colder temperatures.

Insects: While not mammals, certain insects, like the woolly bear caterpillar, enter a state of diapause, which is similar to hibernation. They survive the winter as larvae and resume their development in the spring.

Amphibians: Some amphibians, like certain frogs and salamanders, enter a state of torpor or estivation (a summer equivalent of hibernation) when conditions become unfavorable, such as during droughts or extremely hot or cold periods.